The Gauls affirm that they are all descended from a common Father, Dis,* and say that this is the tradition of the Druids. For that reason, they determine all periods of time by the number, not of days, but of nights,** and in their observance of birthdays and the beginnings of months and years, day follows night.[1] *This is an example of interpretatio romana: What Caesar meant was that the Gauls all claimed descent from a Gaulish God whom he equated with the Roman God Dīs Pater, otherwise known as Rex Infernus or the Greek Pluto (Hades). So the Gaulish equivalent is unknown to us, although a scholium (comment, interpretation) on the Roman poet Lucan’s epic poem commonly known as Pharsalia (properly, De Bello Civili “On the Civil War”) equates Dīs Pater with Taranis, the Gaulish God of Thunder: “Taranis assimilé à Dis pater.”[2] **Hence our older reckoning of time in nights, e.g., “sennight,” (one week; now obsolete) and “fortnight” (two weeks).Upon seeing Caesar’s words, I realized that I had, in fact, read them several times before in the past, but had always been focused on Dīs Pater, rather than on birthdays. Besides Taranis, there are other Celtic candidates for Dīs Pater. Two of the most common are Cernunnos and Sucellos. Anne Ross, in her book Pagan Celtic Britain, and Phyllis Fray Bober, in her article “Cernunnos: Origin and Transformation of a Celtic Divinity,” both propose that Cernunnos, who has connections to wealth and also perhaps to the Underworld, might be the God to whom Caesar was referring.[3] Other suggested possibilities include Teutates, Sucellos Silvanus, Belenos, the Dagda, Donn, Tethra, Bile, Beli Mawr, and Arawn. Obviously, not all of these Gods are Gaulish. Some are Irish, while others are Welsh. So, clearly, some are much more likely candidates for being the equivalent of Dīs Pater than others are. But still, we’re probably unlikely ever to know for certain to which Gaulish God Caesar was referring. Dīs Pater is sometimes paired with the Celtic (or Germanic) Goddess Aericura, whom British archaeologist and academic Miranda J. Aldhouse-Green has called the “Gaulish Hecuba”[4], and whom others have likened to the Greek Goddess Hecate. Aericura may have been associated with grinding or milling (her name may derive from the Latin āēr “air, sky” + the PIE *kuera- “grind, mill flour,” i.e., “Sky Grinder or Miller”). In myth, the foundation of the Cosmic Mill lies at the bottom of the sea (i.e., in the Underworld), while the great mill itself rises to the sky, where it is affixed to the heavens by the “Nowl” (Nail) of the North (which sometimes comes unhinged, leading to the collapse of the mill and utter catastrophe before the mill is reattached with a new nail). Thus, believing themselves descended from the God of the Underworld (and perhaps a Goddess of the Underworld, as well), a chthonic place of darkness and fire, the ancient Celts reckoned time from sundown to sundown, and their new year commenced with the onslaught of winter at Samain (the Dark Half of the Year), associated with the blackthorn tree, which preceded the onslaught of summer at Beltaine (the Light Half of the Year), associated with the hawthorn tree. Despite all this, there was, however, no actual “Celtic Tree Calendar,” as is so often mistakenly believed and promoted these days. I’m sure that many of you have probably seen it posted repeatedly on the Internet (and staunchly proclaimed as “authentic”). But in reality, it had nothing to do with the ancient Celts at all, and was instead fabricated by Robert Graves, author of the wildly inaccurate The White Goddess:

The worst thing about [The White Goddess] — aside from its nearly unreadable nature, as it jumps around from topic to topic with no indication of the relationship between any of the topics at hand — is its influence. Much of what passes as “Celtic” or “Wiccan” or “Druidic” can be found in this horribly muddled text, such as the idea of a Maiden-Mother-Crone goddess (non-existent in Celtic myth), or the goddess-worship. But what is worse is [Graves’s] idea of a “tree calendar” based on the Ogham script. This calendar is almost entirely of his own design (with some help from the 18th and 19th century forgeries and fantasies of men like Davies and Morgannwg). Yet this “Celtic” calendar is touted as a “real” Druidic concept. Do a little research on the Celts, and you will soon learn that this is a complete fabrication.[5]The so-called Celtic Tree Calendar is invariably presented as follows:

• Beth (Birch): December 24 to January 20. • Luis (Rowan): January 21 to February 17. • Nion (Ash): February 18 to March 17. • Fearn (Alder): March 18 to April 14. • Saille (Willow): April 15 to May 12. • Uath (Hawthorn): May 13 to June 9. • Duir (Oak): June 10 to July 7. • Tinne (Holly): July 8 to August 4. • Coll (Hazel): August 5 to September 1. • Muin (Vine): September 2 to September 29. • Gort (Ivy): September 30 to October 27. • Ngetal (Reed): October 28 to November 24. • Ruis (Elder): November 25 to December 22. • December 23 is not ruled by any tree, for it is the traditional day of the proverbial “Year and a Day” in the earliest courts of law.[6]In reality, there’s little or nothing accurate about any of this. To the contrary, out of the twenty letter names for the feda that comprise the Ogam or Ogham (the additional five letter names for the forfeda were not part of the original scheme), “only eight at most are the names of trees. The other names have a variety of meanings.”[7]

Graves even goes so far as to say that these 13 trees were also [the] 13 signs of the zodiac — and that this constitutes the original Celtic Astrology. It does not. (Read “The Fabrication of ‘Celtic’ Astrology” by Peter Beresford (sic21 Lessons of Merlyn [by Douglas Monroe], various “Celtic Wiccan” books published by Llewellyn, and the ridiculous Handbook of Celtic Astrology by Helena Patterson (sic) — which takes this fallacy to a whole new level.[8]In fact, the work of Helena Paterson, especially, has been constantly debunked by knowledgeable Celtic scholars and others. The system she puts forth as genuine Celtic astrology has little or nothing legitimate about it. Ultimately, it’s not even any kind of proper astrological system at all, period. Indeed, it “just falls apart. For it is neither solar/zodiacal nor lunar/almanacal because of its 13 period distribution contrary to the twelve-part zodiacal division of the ecliptic, and not lunar either, because of its duration and fixed dates of periods.”[9] For more on this, see, in addition to Ellis, “Celtic Astrology — A Modern Hoax,” by Michel-Gérald Boutet (iconographer), with comments by Joseph Monard (linguist). In truth, none of these utterly nonsensical systems have anything to do with the ancient Celts at all, much less how they viewed and celebrated birthdays. So, no matter what some may wish or imagine nowadays, none of us was born under any Tree Zodiac sign or Lunar Zodiac sign created and/or developed by the Celts, regardless of what Graves, Paterson, and others like them have written in their books. Rather, it is actually far more likely that Celtic astrology had much in common with Vedic astrology. Ellis, for example, explains that:

…initial researches indicate that the ancient Irish, and, indeed, the ancient Celts, were practicing a predictive form of astrology which paralleled the early Hindu forms, that which we now called Vedic astrology. In other words, a study of linguistic concepts and early cosmological motifs and calendrical philosophies of both Celtic (inclusive of Old Irish) and Sanskrit/Vedic cultures give a path back to the common Indo-European roots of our cultures.[10]Commenting on Ellis’s work, Boutet notes that:

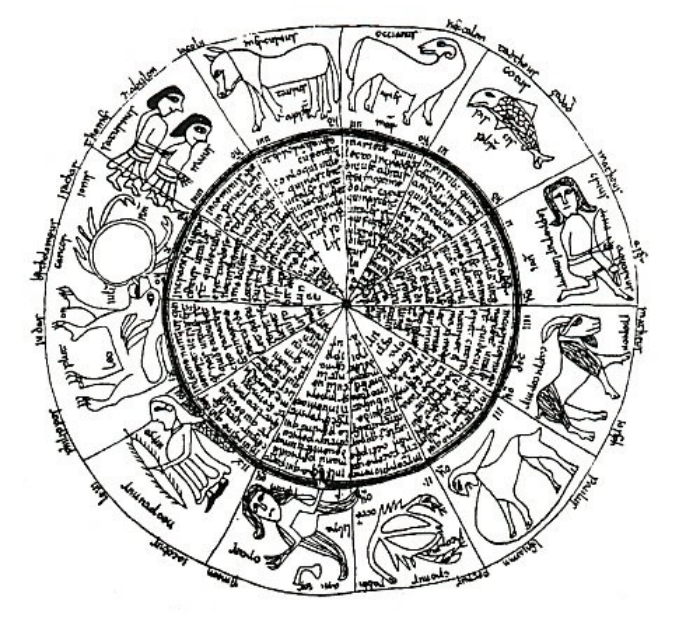

…ancient Celtic astrologers used similar systems as those of the Vedic astrologers. This system was based on the twenty-seven lunar mansions called nakshatras in Sanskrit. [Ellis’s] main argument was found in the motif of the circular palace of King Aillil which was made up of twenty-seven windows and through which he could observe his “Star Wives,” equally twenty-seven. Berresford Ellis also noticed that Aillil had traits similar to the Hindu Soma. This should not come as a surprise, since his queen was none other than Medba, the Mead Queen.[11]Here, in fact, is a copy of an Irish Zodiac illustration contained in “the ancient and fragmentary manuscript of the Liber S. Isidori Hispalensis de Natura Rerum [Isidor of Seville’s Book on the Nature of Things] which belongs to [the] public library of Basel and is written in Irish characters [although the text itself is in Latin].”[12] We can see that with a few exceptions, this early Irish Zodiac wheel more or less resembles and follows our own modern one:

It’s probably fair to assume that the manuscript which contains the Irish zodiac drawing [just above] comes from the 8th or 9th century at the latest. The manuscript indicates that judicial astrology was not unknown within 9th century Irish centres of learning. The co-existence of biblical and Graeco-Roman mythological references is noteworthy.[13]

While, clearly, we know a great deal about astrology and one’s birth, we don’t actually know much about some other birthday traditions. For instance, we don’t know for certain when the custom of birthday cakes began. Many date the origin of birthday cakes to the Romans. In “classical Roman culture, cakes were occasionally served at special birthdays and at weddings. These were flat circles made from flour and nuts, leavened with yeast, and sweetened with honey.”[14] The Celts also had cakes, so it’s possible that they did serve them on special occasions, such as birthdays, as well.

Candles on birthday cakes are often credited to the Greeks, who used them “to honor the goddess Artemis’ birth on the sixth day of every lunar month. The link between her oversight of fertility and the birthday tradition of candles on cakes, however, has not been established.”[15] But still, it is thought that lit candles would be placed on the cake to represent the glowing Moon in the night sky, and that their smoke carried wishes and prayers to the sky-dwelling Gods. This actually does seem entirely reasonable in light of the fact that even today, we continue to make a wish when we blow out the candles on our birthday cake, thereby causing them to send their smoke skyward as we hope for our wish to come true.

Did the ancient Celts, like the Greeks, put candles on their cakes, too? We don’t know. But still, the Celts were flame tenders, so perhaps there was at least one candle lit to honor the Sun on the day of one’s solar return. I like to think so, anyway.

Finally, I personally find it quite interesting that birthdays are celebrated with a cake. I wonder if there is some connection between the cake, its flour, the grinding of the grain, the great Cosmic Mill, and the turning of Time….

Food for thought, perhaps, the next time you dig into your own birthday cake!

Blessings!

APs Rhianwen Bendigaid

Footnotes:

[1] Caesar, Julius, De Bellum Gallico VI:18.

[2] Vendryes, Joseph (1958). Études celtiques (in French). Les Belles Lettres, p. 55.

[3] “Which Celtic God Is the Equivalent of the Roman Dis Pater?” Mythology & Folklore Stack Exchange. Web. 5 March 2023.

[4] Green, Miranda, The Gods of the Celts. Sutton Publishing, 2004, p. 124.

[5] Jones, Mary, “The White Goddess: A Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth.” Jones’s Celtic Encyclopedia. Web. 5 March 2023.

[6] Jones, Mary, “The Celtic Tree Calendar.” Jones’s Celtic Encyclopedia. Web. 5 March 2023.

[7] “Ogham.” Wikipedia. Web. 5 March 2023.

[8] Jones, Mary, “The Celtic Tree Calendar.” Jones’s Celtic Encyclopedia. Web. 5 March 2023.

[9] Boutet, Michel-Gérald (iconographer) and Monard, Joseph (linguist), “Celtic Astrology — A Modern Hoax.”

[10] Ellis, Peter Berresford, “Early Irish Astrology: An Historical Argument.”

[11] Boutet, Michel-Gérald, “Druuidica Prinnion (Druidical Astrology),” commenting on Ellis, Peter Berresford, “Our Druid Cousins.”

[12] Sheeran, Bill, “An Irish Zodiac Preserved in a Library at Basle (sic).” Radical Astrology. Web. 5 March 2023. Citing Crawford, Henry S., “An Irish Zodiac Preserved in a Library at Basel,” Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland (Vol.LV, pp. 130-135), 1925.

[13] Ibid.

[14] “Birthday Cake.” Wikipedia. Web. 5 March 2023.

[15] Ibid, citing Rusinek, Marietta (2012). “Cake: The Centrepiece of Celebrations.” Celebration: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2011. Oxford: Prospect Books, pp. 308–315.